1. What is the LIRA and Why Does it Gain Popularity?

Pensions serve the essential role of replacing or adding on to income in retirement. Despite being a very useful tool, their terms can be confusing at times, and this can make it difficult to take full advantage of them. We will take a look at a common retirement account, the Locked In Retirement Account (LIRA), and try to bring some clarity as to how the account works, the different options when it comes to withdrawing funds, and why they are becoming increasingly common in recent times.

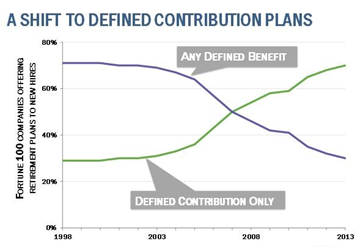

In short, a Locked-In Retirement Account (LIRA) is a registered pension fund that does not allow withdrawals until retirement; the funds cannot be taken out of the account while they are locked in. The rise of the LIRA is essentially a result of a general shift towards defined contribution plans (DCPs) instead of the defined benefit plans (DBPs).

2. DBP and DCP Comparison

The DCP and the DBP are the two available types of pensions in Canada, and while they are both created to generate pension at retirement, they take completely different approaches for achieving that. As their names suggest, the defined benefit plans (DBPs) include a predictable income once the employee retires, whereas defined contribution plans (DCPs) will have employees contribute a set amount to the plan periodically over time. DBPs will typically have a schedule where a certain percentage of the pension unlocks over time. For instance, an employee may need to work at the company for 25 years before unlocking the full pension. On the other hand, with DCPs, the employee builds up a balance through their contributions and market returns, and the plan’s asset base gets distributed once the employee retires.

A key advantage to DBPs is that the investment risk stays with the employer who must ensure there is sufficient money for the lifetime payouts in the future. Additionally, these payouts are typically indexed to inflation to conserve purchasing power. This lack of uncertainty helps make retirement planning much more straightforward.

However, there are some important drawbacks to DBPs. As already noted, it is common for these plans to include a clause that employees must work a certain number of years before they can receive the full pension amount. This may lead to some employees working longer than they would otherwise so that they get the full amount of the pension. Moreover, the company that issued the DBP can go bankrupt or fail to manage their investments effectively, in which case they would be unable to meet their pension obligations. Finally, if the pension is not indexed to inflation, the retirement income it produces could lose purchasing power over time, leading pensioners to underestimate the need for additional retirement income sources.

With a DCP the employees contribute a set amount without knowing what the final benefit in retirement will be. The employee makes the investment decision from the choices offered by the pension plan carrier, and the contributions are sometimes matched by employers up to a certain amount. For example, if the employee contributes 5% of their salary, the employer will contribute an additional 2%. Defined contribution plans work very similarly to a group RRSP; however, by matching employee contributions, employers make it difficult to generate better returns by managing the savings on their own, thus incentivizing people to use their pension plan. Another key benefit of DCPs is that contributions generally vest within two years of joining the plan. Any payment to the plan belongs entirely to the employee, so if they leave the company, the money they contributed leaves with them.

However, there are some notable disadvantages to DCPs, namely that the employees bear the risk of market volatility on the final payout amount in retirement. Additionally, the investment choices provided by these plans tend to be very limited, and they generally include expensive mutual funds that historically underperform market indexes.

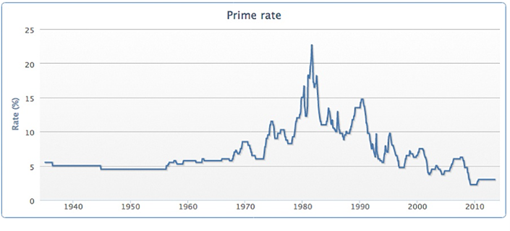

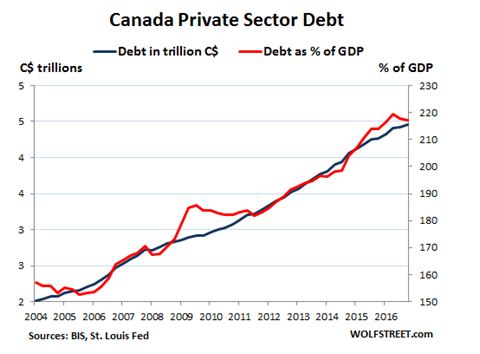

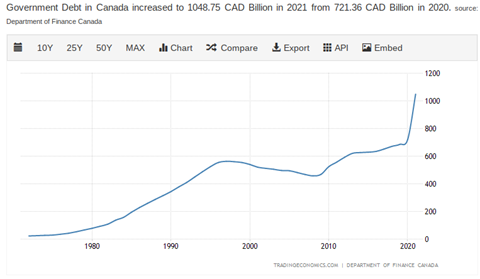

The shift from DBPs to DCPs we are experiencing today is mostly a result of the unwillingness of employers to bear the investment risk associated with the DBPs, and the low interest rates in Canada. The DBPs act like fixed income securities (since they provide a pre-determined fixed payouts at retirement), and the low levels of the interest rates undermine the return on the investments, making it hard for employers and corporations to meet their pension obligations to employees. The interest rates are purposefully kept low by the Bank of Canada, which keeps the overnight rate* low (see Figure 1) because of the record-high levels of government and public debt, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Any increase in the interest rates would mean a bigger burden on debt on all highly leveraged individuals and organizations, which would in turn hard the overall economic growth.

The lack of yield on fixed income products has led DBPs to trend towards being underfunded, which casts doubt on whether these employers will actually pay out what they have committed to. For example, Bombardier, a Canadian aviation company, is facing a pension deficit of $2.5 billion dollars as of 2019. Since fixed income products can no longer be relied on, pensions are being invested in riskier areas of the market, such as private equity and stocks. While this has been effective in the past decade due to a prolonged bull market in equity valuations, this could result in underperformance during times of market distress, leading to difficulty meeting obligations. The chart below demonstrates the trend towards DCP’s.

Figure 1. Prime Rate in Canada

Figure 2. Canada Private Sector Debt

Figure 3. Canada Government Debt

Figure 4. DCP and DBP Trend

* The overnight (prime) rate is the rate set by the Bank of Canada for short-term lending and borrowing. It is a key determinant in the level of the interest rates in the economy.

3. Locked-In Retirement Accounts

The shift towards DCPs has implications for Canadian retirees. Employees are increasingly likely to have vested positions in pension plans from their existing or past companies in the form of Registered Pension Plans (RPP). When an employee leaves their employer, the funds in their RPP are transferred into a locked-in account.

A Locked-In Retirement Account (LIRA) is a registered pension fund that does not allow withdrawals until retirement except in special circumstances like eviction or a failure to meet debt obligations. Unlike the RRSP, where funds can be cashed at the owner’s discretion, cash cannot be taken out of the account while the funds are locked in. LIRAs were created to hold funds that are transferred from a pension plan where the employee is no longer a member of. This can be the result of the beneficiary leaving their job, splitting the pension with a spouse, or wanting to leave funds to an heir.

A Locked-In Retirement Savings Plan (LRSP) is very similar to a LIRA, except for the fact that an LRSP is regulated federally, whereas a LIRA is regulated provincially. This means that for provincially regulated pension plans, the funds will be transferred to a LIRA, whereas federally regulated plans transfer funds over to a LRSP.

4. Unlocking a LIRA

Once funds are transferred over from an RPP to a LIRA, they cannot be withdrawn until the age of 55. However, even at that age, there are several rules regarding the withdrawals from the LIRA. At the age of 55, a LIRA holder can consider unlocking up to 50% of the balance. If they decide to unlock the funds, they cannot withdraw directly from the LIRA. Instead, all the funds must first be transferred to a Restricted Life Income Fund (RLIF). The 50% maximum is based on the RLIF account value. Therefore, the entire LIRA would need to be transferred in order to withdraw the maximum amount. The unlocking must occur within 60 days of the deposit to the LIF (life income fund).

The 50% can either be withdrawn as cash, which would be fully taxable, or it can be transferred into another RRSP (registered retirement savings plan), where it will continue to grow tax free, but is accessible if the funds need to be withdrawn. Deciding whether to withdraw a LIRA in the form of cash or a transfer to an RRSP depends mainly on liquidity needs and the carry forward room. If a beneficiary would need the cash in a short period of time, withdrawing directly to cash makes sense, however if the cash is not urgently needed and there is enough room in the RRSP, it would be more profitable to let these funds grow tax free in an RRSP until they are needed.

For the remaining balance of the RLIF, a minimum amount must be withdrawn each year. For example, if one is 55 years old when the account is unlocked, at the start of the following year 2.86% of the RLIF must be withdrawn. Each year these minimum amounts increase until the RLIF no longer has a remaining balance.

If someone does not want the annual withdrawals that come after unlocking a LIRA, they can transfer the remaining funds to a Restricted Locked-In Savings Plan (RLSP), where funds cannot be withdrawn, and remain tax deferred until the age of 71. The only difference between a LIRA and an LRSP is that the LIRA has yet to be unlocked whereas with an RLSP an unlock is no longer possible.

5. LIF Options and Distribution Rules

Once the RLSP account owner reaches the age of 71, they must decide whether to convert their RLSP into a LIF or to purchase an annuity. With a LIF, account holders are restricted in how much they can withdraw each year. There are maximums and minimums set in place by the provincial government to ensure that the savings last for the course of the individual’s retirement. For example, at the age of 75, the LIF minimum withdrawal is 5.82% of the account balance and the maximum is 9.7%. Once a retiree reaches the age of 89, they can withdraw the entire balance of the account. All withdrawals from the LIF are taxable as regular income.

The other option is to purchase a life annuity. With this option, the account holder receives a guaranteed monthly payment, however they forgo control of how the funds are invested and generally no money is passed down to heirs when the account holder passes away.

The two options offer different withdrawal schedules, and different investors may have a different preference depending on their personal needs. For someone who is risk averse and feels they may have a high life expectancy, the life annuity would make sense as it provides guaranteed income for the remainder of retirement. However, someone else may assign a lot of value in passing down money to heirs or having control over their own investments, in which case the LIF would be more suitable.

6. Conclusion

The trend towards DCPs has made LIRAs much more common in recent times. Despite this, LIRAs have some complicated terms when it comes to withdrawals that can make it difficult to understand what is optimal for your specific situation. Deciding when to unlock the funds depends on the need for liquidity and the availability of other sources of income in retirement, which can be difficult to predict as unexpected expenses may arise. Transferring the LIRA funds into an RRSP after the unlock is a good way to benefit from the tax shelter while still having access to the funds given there is enough room in the RRSP. The remaining funds not immediately transferred (or taken out as cash) have to follow a specific withdrawal schedule. The withdrawn funds may be transferred an RLSP, from where the individual can deposit into a LIF use the proceeds to purchase a life annuity once they reach the age of 71.

With decisions as important as this, it can be very beneficial to bring in professional help from an investment advisor or a financial planner. Advisors can help create a retirement income plan that puts this decision in context, and highlights whether liquidity is a potential issue that needs to be considered in retirement. In the end though, it’s up to you to make the decision, so it’s always useful to have a high-level understanding of how these accounts work in order to ensure you are taking advantage of them to the fullest.

Author: Rodrigo Anzola

Editor: Alexander Natchev

Sources

- “The Process of Unlocking a LIRA Account”, 2022

- Fidelity Investments. “Defined benefit vs defined contribution: What is the best pension”

- Bipartisan Policy Centre. “Defined Benefit Plans: Where’d they go?”, 2014

- Savvy New Canadians. “LIRA, LRSP, LIF, LRIF, and PRIF: What’s Their Place in Your Retirement Planning?”, 2022

- Mortgage Intelligence. “Interest Rates Are Going To Go Crazy Soon”, 2015

- Wolf Street. “Whose Private-Sector Debt Will Implode Next: US, Canada, China, Eurozone, Japan?”, 2017

- Trading Economics. “Canada Government Debt”, 2021